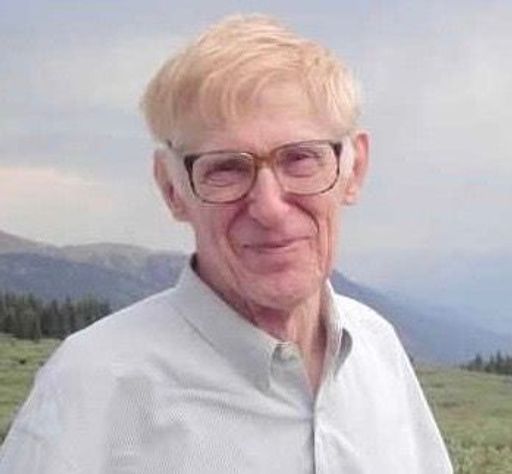

Gerald Chapman

July 20, 1927 — June 30, 2020

If our Dad were writing this obituary, the first thing he would want you to know about him is how lucky he was during his life. (The very first thing we might have said is how hard he tried to hold onto that life, and how ardently he fought against death despite the serious pain he had suffered since 1999 from a spinal stenosis so severe that by the end it had curved his back into the shape of a serpent.) Born in 1927 in the small East Texas town of Rusk, Dad grew up in a world still overshadowed by the Civil War. His parents, Gerald Benson Chapman and Eunice Wester Chapman, were both educated at nearby Rusk College, and his father later served as the Rusk Superintendent of Schools. However, higher education was by no means a given in the Rusk of his youth, nor was it necessarily expected that he would ever leave that world to go elsewhere. But Dad was exceptionally intelligent, passionate about language, and an avid reader. As a boy, he once began what he intended to be a history of England; unfortunately, as he later said ruefully, he only "made it to the Anglo-Saxon period." (It tickled him enormously that one of us later became a medievalist specializing in early medieval Britain and Ireland.) His first lucky break was a scholarship for valedictorians that took him to the University of Texas for his freshman year; his second was the GI Bill, which allowed him after discharge from the Navy to finish his undergraduate degree and begin graduate study at Southern Methodist University in Dallas. It was there that he met and married our mother, Ruth Bradbury Rimmer, a fellow graduate student from Dallas, on New Year's Eve of 1950; they would later divorce in 1967.

The stroke of luck that really changed his life, however, was a summer seminar at SMU, taken almost on a whim, that resulted in a fully funded fellowship to study at Harvard University for his Ph.D. There he had the good fortune to study with the renowned scholar Jackson Bate, who became a revered mentor and lifelong friend; simply put, this was for him one of the most formative times in his life. He finished his doctoral degree in 1957, and between then and 1961, taught variously at Harvard and Northwestern University in Evanston, Illinois, where his children Robin and Wes were born in 1955 and 1957, respectively. In 1961, he moved to the University of Texas, but in 1962, his eye was caught by an advertisement for an English professorial position and Chair at the University of Denver. On his visit there, he fell in love with the people and the place, and he thrilled to the opportunities DU offered for professional growth. In the years of his chairmanship, he doubled the size of the department, adding writers and scholars like Es'kia Mphahlele and Robert Richardson to an already world-class program that included prize-winning novelist John Williams and renowned writer and translator Burton Raffel. In 1966, he worked with Williams to found the Denver Quarterly , then and now a highly respected journal of literature and literary criticism. During this time, he published the books for which he himself would be best known: Essays on Shakespeare (Princeton University Press, 1965, reprinted 2016); Literary Criticism in England, 1660-1800 (Knopf, 1966); and Edmund Burke: The Practical Imagination (Harvard University Press, 1967). From 1967-1976, he served as Phipps Professor, and in 1976 won what was for him one of his most prized awards, the Distinguished Teaching Award from the University of Denver.

Those were halcyon days, and when he retired in 2003, he was sorry to leave them behind. On the other hand, his retirement allowed him to pursue in a more focused way the activities he had loved all his life: music, plays, movies, and especially traveling. He had never traveled out of the country until his forties, but once he started, he kept going until he could literally travel no longer. He loved Europe-the three of us had a wonderful trip to Ireland in 1999 where Dad, always the ginger-haired romantic hero in appearance, had to fend off the advances of a lonely B & B hostess (whose husband, it should be said, was right downstairs). He combined his mainland European trips with travel to other locales such as China, Israel, Egypt, and Russia. As those who have ever visited his apartment will know, souvenirs from all over the world vied for space with the approximately 10,000 books (!) he left behind when he died.

His last and perhaps greatest stroke of luck came in 2008, when Elspeth MacHattie, a long-time friend, became his life partner. They shared so much while he was healthy: she introduced him to ballet, and together they enjoyed an active life full of music, literature, theatre and art. It is impossible for us to describe how important she was and remained to him throughout the rest of his life. She was and is important to us as well: we cannot imagine surviving the difficult final years of our father's life without her unfailing kindness, generosity, intelligence, and practical good cheer. In addition to Elspeth, he leaves behind his children, Robin Chapman Stacey, a professor of History at the University of Washington, and Wes Chapman, a professor of English at Illinois Wesleyan University; a son-in-law, Robert Stacey, Dean of Arts and Sciences at the University of Washington; and two grandchildren, Anna Chapman Stacey, a third-year law student at Georgetown University, and Connor Wester Alisson, a computer science major in his final year at the University of lllinois, Springfield. A third grandchild, Marine Sergeant William Chapman Stacey, was killed in Afghanistan in 2012. Also an important part of his life was his former daughter-in-law, Alison Kay Sainsbury. Additionally, he leaves behind a loving sister-in-law, Anita Chapman, of Longview, Texas, and a number of nieces and nephews, also in Texas. His brother, Michael Chapman, predeceased him in 2012.

And finally, things we loved most about Dad, or that drove us crazy but that we loved anyway: his profound and ultimately Shakespearean vision of human nature, with all its glories and limitations; his passion for language and for puns, which has doomed his children and grandchildren to inflicting pun wars on even distant acquaintances; his endless desire for chocolate, which was always in plentiful supply during the prolonged and curse-ridden Hearts games we played every time we got together; his hoarding of books, books, books, and other stuff too; the fervent belief in democracy that led him in his eighties to march with his walker in support of social and economic equity; and finally his humor, which we hope will give us strength to face the future without him.

Given the restrictions imposed on us all by the pandemic, no memorial service is planned at this time. However, donations in lieu of flowers may be given to the University of Denver, Department of English Gift Fund, in Memoriam Gerald Chapman. The address for the University of Denver Department of English and Literary Arts is Sturm Hall, Room 495, 2000 E. Asbury Ave, Denver, CO 80208.

Guestbook

Visits: 95

This site is protected by reCAPTCHA and the

Google Privacy Policy and Terms of Service apply.

Service map data © OpenStreetMap contributors